Climatology is the study of Earth's long-term weather patterns and the natural and human factors that influence them. Most positions require at least a master's degree in atmospheric sciences or environmental science. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, environmental scientists and specialists (the occupational category that includes climatologists) earned a median salary of $76,530 in 2023, with 6% projected growth through 2033.

Climate science sits at the intersection of environmental urgency and scientific discovery. If you're considering a career in climatology, you're looking at a field that combines rigorous scientific research with meaningful impact on our planet's future. Climatologists study everything from ancient ice cores revealing Earth's climate history to current atmospheric data showing how human activities alter global weather systems.

This comprehensive guide covers what climatology is, how to become a climate scientist, career prospects and salaries, educational requirements, and the fascinating work climatologists do to understand our changing planet. Whether you're a prospective student exploring environmental science programs or someone considering a career change, you'll find clear pathways and realistic expectations for this growing field.

On This Page:

- What Climatology Is

- How Climatology Differs From Meteorology

- How to Become a Climatologist

- Climatology Career Outlook

- What Climatologists Do

- Natural Climate Drivers

- Human Impacts on Climate

- A Brief History of Climatology

- Subdisciplines of Climatology

- Future Challenges for Climatology

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Key Takeaways

What Climatology Is

Climatology (also known as climate science) is the study of Earth's weather patterns and the systems that cause them. From ocean oscillations to trade winds, atmospheric pressure systems, airborne particles, and even Earth's orbital variations-all these factors affect climate. The word "climatology" comes from the Greek klima (zone or area) and logia (study).

Climatology (also known as climate science) is the study of Earth's weather patterns and the systems that cause them. From ocean oscillations to trade winds, atmospheric pressure systems, airborne particles, and even Earth's orbital variations-all these factors affect climate. The word "climatology" comes from the Greek klima (zone or area) and logia (study).

Climatologists today focus heavily on understanding and addressing global warming, but the science encompasses much more. Climate scientists examine natural climate variability, predict future climate scenarios, study historical climate patterns, and work to understand the complex interactions between atmosphere, oceans, land surfaces, and living systems.

Until relatively recently, climatology was considered a specialized but understated area of science. Since it became clear that human actions are changing Earth's climate, the field has gained prominence internationally. Most governments now have departments dedicated to climate change mitigation and adaptation planning.

How Climatology Differs From Meteorology

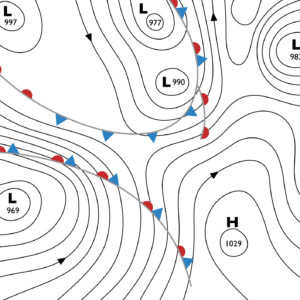

Climatology is not meteorology, though both fields study weather and atmospheric processes. The key differences:

- Timescale: Meteorology examines short-term weather (days to weeks) while climatology studies long-term patterns (decades to centuries)

- Focus: Meteorologists forecast what the weather will do tomorrow; climatologists analyze what climate patterns reveal about Earth's past and future

- Geographic scope: Meteorology concerns specific regions and local weather systems; climatology examines large-scale or global climate patterns

- Data use: Both use satellites and atmospheric measurements, but climatologists analyze much longer data sets to identify trends and cycles

Many climatologists start their education in meteorology or atmospheric science before specializing in climate research. If you're interested in the atmospheric sciences, exploring meteorology degree programs can provide a strong foundation for climate science work.

How to Become a Climatologist

The path to a climatology career requires strong academic preparation and typically advanced degrees. Here's what you need to know about educational requirements and the skills you'll develop.

Educational Pathways

Bachelor's Degree (4 years): Most aspiring climatologists start with a bachelor's degree in atmospheric science, environmental science, meteorology, physics, or a related field. Your undergraduate coursework should include calculus, statistics, physics, chemistry, and computer programming. Some universities offer specific climatology concentrations within environmental science programs.

Master's Degree (2-3 years): A master's degree in climatology, atmospheric sciences, or environmental science is typically the minimum requirement for professional climatologist positions. Graduate programs emphasize climate modeling, statistical analysis, research methodology, and specialized study in areas like paleoclimatology or climate dynamics. Most programs require a thesis based on original research.

Doctoral Degree (4-6 years): A PhD is essential for research positions, university faculty roles, and senior positions at federal agencies. Doctoral students conduct extensive original research, often focusing on specific aspects of climate science like ocean-atmosphere interactions, climate modeling, or impacts of climate change on ecosystems.

Skills Required for Climate Science

Successful climatologists develop both technical and interpersonal skills. Technical skills include advanced mathematics and statistics, programming languages (Python, R, MATLAB, Fortran), data visualization, atmospheric physics and chemistry understanding, GIS for spatial analysis, and research methodology. Equally important are soft skills: scientific writing, communication abilities to explain complex patterns to non-technical audiences, collaboration for interdisciplinary research, critical thinking, attention to detail, and patience for long-term projects.

Climatology Career Outlook

Climate science offers stable career prospects with competitive salaries and diverse employment opportunities. Understanding the financial and employment landscape helps you make informed decisions about this career path.

Salary Information

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, environmental scientists and specialists (the occupational category that includes climatologists) earned a median annual salary of $76,530 as of May 2023. However, salary varies significantly based on several factors:

Salary Distribution: The lowest 10% earned less than $47,940, while the highest 10% earned more than $129,450. The 25th percentile was $59,990, and the 75th percentile was $100,590.

Salary by Employment Sector (May 2023 BLS data):

- Federal government: $105,990 (highest-paying sector)

- Architectural, engineering, and related services: $76,140

- Management, scientific, and technical consulting: $76,140

- State government: $70,860

Additional factors affecting salary include education level (PhD holders command higher salaries), geographic location (metropolitan research hubs offer premium compensation), experience (entry-level typically $50,000-$60,000; senior positions $100,000+), and specialization (climate modelers with programming skills often command premium salaries).

Job Growth and Employment Projections

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 6% employment growth for environmental scientists and specialists from 2023 to 2033, about as fast as the average for all occupations. This occupational category includes climatologists along with other environmental science professionals. The projection translates to approximately 7,000 job openings annually over the decade.

Growth drivers include increased governmental focus on climate change, expanded environmental regulations requiring compliance analysis, growing demand for climate risk assessment in business and insurance sectors, and rising need for climate data in agriculture, water management, and urban planning. Competition for positions remains strong, particularly for research roles at prestigious institutions, with PhD holders having the best prospects.

Where Climatologists Work

Climate scientists find employment across federal agencies (NOAA, NASA, EPA, Department of Defense, USGS, Department of Energy-about 30% of environmental scientists work in federal government); research institutions and academia (universities, national laboratories, think tanks); private sector (environmental consulting, insurance companies, energy firms, agricultural companies, technology platforms); state and local government (climate adaptation planning, water resources, environmental management); and non-profit organizations (environmental advocacy, conservation, international development).

What Climatologists Do

Climate scientists engage in diverse activities depending on their specialization and employment sector. Daily work typically involves a combination of data analysis, research, modeling, and communication.

Core responsibilities include collecting and analyzing climate data from satellites, weather stations, ocean buoys, and ice cores; developing and running computer models to simulate climate processes; conducting field research; publishing findings in scientific journals; collaborating with scientists from other disciplines like geology, environmental health, ecology, and oceanography; advising policymakers; writing grant proposals; and mentoring graduate students.

Most climatologists split their time between office work and occasional fieldwork. Office work involves computer modeling, data analysis, writing research papers, and meetings. Fieldwork might include collecting ice core samples in polar regions, measuring atmospheric conditions from research vessels, or installing monitoring equipment in remote locations. The ratio varies by specialization-paleoclimatologists might spend several months in the field, while climate modelers work almost exclusively with computers.

Natural Climate Drivers

Understanding climate requires studying both natural variability and human impacts. Climate science examines numerous natural processes that influence Earth's weather patterns over various timescales.

Understanding climate requires studying both natural variability and human impacts. Climate science examines numerous natural processes that influence Earth's weather patterns over various timescales.

Ocean-Atmosphere Oscillations

Ocean-atmosphere oscillations are periodic variations in sea surface temperatures and atmospheric pressure that significantly impact global weather patterns. These oscillations occur naturally and can influence the climate for months or even decades.

El Niño and La Niña (ENSO): The El Niño-Southern Oscillation occurs in the equatorial Pacific roughly every 3-7 years. El Niño brings warmer ocean temperatures and altered precipitation patterns globally, while La Niña brings cooler temperatures with opposite effects. ENSO impacts agriculture, water resources, and extreme weather frequency across the Pacific and far beyond.

Other Major Oscillations: The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) affects European and North American weather. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) operates over 20-30-year cycles, influencing marine ecosystems and long-term drought patterns. Several other oscillations-including the Madden-Julian Oscillation, North Pacific Oscillation, and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation-create complex interactions that climatologists work to understand and predict.

Solar Activity

The sun's energy output fluctuates over time, affecting Earth's climate. Solar temperature and radiation levels vary in cycles, with well-documented 11-year solar cycles and longer-term variations. Historical climate events like the Medieval Warm Period (900-1300 CE) and the Little Ice Age (1300-1850 CE) correlate with periods of increased and decreased solar activity, respectively. However, solar variability cannot account for the observed magnitude of recent warming, which is why climatologists focus heavily on greenhouse gas emissions as the primary driver of current temperature increases.

Volcanic Activity

Large volcanic eruptions can temporarily cool Earth's climate by injecting massive amounts of sulfur dioxide and ash into the upper atmosphere, reflecting sunlight back to space. The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora caused "the year without a summer" in 1816. The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo cooled global temperatures by about 0.5�C for 1-2 years. Some researchers have proposed that periods of intense volcanic activity may have contributed to the Little Ice Age, though evidence remains debated. While individual eruptions cause short-term cooling, the long-term climate impact is minimal compared to greenhouse gas accumulation.

Human Impacts on Climate

Since the Industrial Revolution, human activities have become the dominant driver of climate change. Climatologists study these anthropogenic (human-caused) factors to understand current warming and project future scenarios.

Greenhouse Gases

Greenhouse gases trap heat in Earth's atmosphere, creating a warming effect. The primary greenhouse gases and their sources include carbon dioxide (CO₂), the most significant from human activity, released by burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and cement production (atmospheric CO₂ has increased from 280 parts per million pre-industrial to over 420 ppm in 2024 according to NOAA); methane (CH₄) from agriculture, natural gas production, landfills, and wetlands; nitrous oxide (N₂O) primarily from agricultural fertilizers; water vapor (the most abundant greenhouse gas, controlled by temperature rather than direct emissions); and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), once common in refrigerants, now heavily regulated after the Montreal Protocol (1987) successfully reduced emissions.

Deforestation and Land Use

Forests act as carbon sinks, absorbing CO₂ through photosynthesis. Cutting down forests without replacement reduces Earth's capacity to absorb carbon emissions. Deforestation also releases stored carbon from trees and soil. Additionally, replacing forests with agriculture or urban development changes local and regional climate through altered water cycles, surface reflectivity (albedo), and heat absorption patterns.

Ocean Impacts

Oceans have absorbed approximately 30% of human-caused CO₂ emissions since the Industrial Revolution, slowing atmospheric warming but causing ocean acidification. This acidification threatens coral reefs, shellfish, and marine food webs. Climatologists work closely with marine scientists to understand these interconnected systems and predict future changes.

A Brief History of Climatology

Modern climatology emerged gradually from observations by ancient naturalists to today's sophisticated computer modeling and satellite monitoring.

Ancient to Early Modern Period

Greek philosophers Aristotle and Theophrastus made early observations about how climate affects landscapes and vegetation. Theophrastus noted how draining swamps could alter local temperatures-an early recognition of human impacts on local climate. However, systematic climate science wouldn't emerge for nearly 2,000 years.

The Industrial Revolution Era (1800s)

The 19th century brought crucial developments. Geologists studying rock formations and fossils realized Earth's climate had changed dramatically over time-deserts had been tropical swamps, and temperate regions had been covered in ice. The concept of ice ages emerged from evidence of past glaciation.

In 1896, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius published the first calculations suggesting that burning fossil fuels could warm the planet by increasing atmospheric CO₂. However, with relatively low emissions at the time, this was viewed as a curiosity rather than a threat.

20th Century Developments

The mid-20th century saw climatology mature as a distinct discipline. Researchers discovered that oceans could absorb CO₂, identified multiple past ice ages through geological evidence, and recognized that solar output varied (disproving the "solar constant" theory). The 1958 start of continuous CO₂ measurements at Mauna Loa Observatory provided the first clear evidence of rising atmospheric carbon.

The 1960s and 1970s marked an important period for environmental science. Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962) raised public awareness of environmental issues. The first Earth Day (1970) and the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (1970) reflected growing concern about human environmental impacts. Climate scientists began distinguishing between natural climate cycles and anthropogenic changes.

The Modern Era (1980s-Present)

The 1980s established scientific consensus on human-caused climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was founded in 1988 to assess climate science and provide policy guidance. Ice core data from Greenland and Antarctica revealed dramatic past climate changes and confirmed the relationship between atmospheric CO₂ and temperature.

The 21st century has brought unprecedented computational power, satellite monitoring, and big data analytics to climate science. Recent years (2023-2024) saw record global temperatures, with significant heat waves, wildfires, and extreme weather events. Modern climatologists use artificial intelligence and machine learning to improve climate models, analyze massive datasets, and predict regional climate impacts with increasing precision.

Subdisciplines of Climatology

As climatology has grown, numerous specialized areas have emerged. Understanding these subdisciplines helps you identify potential career paths and research interests.

As climatology has grown, numerous specialized areas have emerged. Understanding these subdisciplines helps you identify potential career paths and research interests.

Applied Climatology

Applied climatologists use current climate data to solve practical problems. They might help farmers plan crop selection based on shifting growing seasons, advise urban planners on heat island mitigation, or assist insurance companies in assessing climate risk. This field has roots in ancient civilizations-Egyptian agriculture depended on understanding Nile River flood patterns-but modern applied climatology uses sophisticated modeling and real-time data to address contemporary challenges.

Paleoclimatology

Paleoclimatologists study Earth's ancient climates using proxy data: ice cores, tree rings, coral records, lake sediments, and fossilized pollen. This research reveals how Earth's climate has changed over millions of years, including at least five major ice ages and multiple rapid warming events. Paleoclimatology provides crucial context for understanding current climate change-we know Earth has experienced much higher CO₂ levels in its distant past, but never have they risen this rapidly while humans have existed.

Climate Modeling and Dynamic Climatology

Climate modelers develop and refine computer simulations of Earth's climate system. These models incorporate atmospheric physics, ocean circulation, ice dynamics, vegetation feedbacks, and human emissions to project future climate scenarios. Dynamic climatology takes a holistic approach, integrating quantitative data from all climate-related sciences to understand the complete climate system.

Regional Climate Specializations

Several subdisciplines focus on specific aspects of the climate system. Bioclimatology studies how climate affects living organisms and ecosystems, including the migration of disease vectors, changes in species ranges, and agricultural impacts. Hydroclimatology examines climate's effects on water resources-precipitation patterns, drought, flooding, sea level rise, ocean acidification, and the global water cycle. Boundary-layer climatology focuses on the lowest layer of the atmosphere where weather occurs. Synoptic climatology studies atmospheric circulation patterns that create different weather types. Urban climatology investigates how cities create microclimates through heat islands, altered precipitation, and air quality changes.

Many climatologists work across multiple subdisciplines, and the field increasingly requires interdisciplinary collaboration with ecologists, oceanographers, public health experts, and social scientists.

Future Challenges for Climatology

As we move deeper into the 21st century, climatology faces both scientific and societal challenges.

Improving Climate Models

Despite tremendous progress, climate models still struggle with certain processes. Clouds remain difficult to model accurately. Regional precipitation predictions have high uncertainty. Tipping points-thresholds beyond which climate change becomes self-reinforcing-are poorly understood. Future climatologists will work to reduce these uncertainties using better data, more powerful computing, and improved understanding of fundamental climate processes.

Understanding Climate Impacts on Society

Climatologists increasingly collaborate with social scientists, public health experts, and economists to understand how climate change affects human systems. This includes studying climate impacts on food security in marginal landscapes, how changing disease vector ranges affect public health, climate migration patterns, economic costs of extreme weather, and environmental justice issues as climate impacts disproportionately affect vulnerable populations.

Big Data and Artificial Intelligence

Climate science now generates petabytes of data from satellites, ground measurements, ocean buoys, and model outputs. The challenge isn't collecting data but extracting meaningful insights. Modern climatologists use machine learning to identify patterns, improve model predictions, and process unprecedented data volumes. However, data quality remains critical-AI can only work with the data it receives, and climatologists must carefully distinguish signal from noise.

Climate Solutions Research

Beyond understanding climate change, climatologists increasingly study potential solutions: How quickly can renewable energy replace fossil fuels? What are the realistic limits of natural carbon sinks? How can we adapt infrastructure to inevitable climate changes? What are the risks and benefits of proposed geoengineering approaches? How do we balance development needs with climate mitigation?

Science Communication

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing climatology isn't scientific but communicative. Climate scientists must effectively communicate complex, uncertain information to policymakers and the public. This requires skills in public speaking, writing, media engagement, and navigating complex debates. Many graduate programs now include training in science communication.

Frequently Asked Questions

What degree do I need to become a climatologist?

Most climatology positions require at least a master's degree in atmospheric sciences, climatology, or environmental science. Entry-level roles may accept bachelor's degrees in meteorology or atmospheric science. Research positions, university faculty, and senior federal agency roles typically require a PhD. Essential undergraduate coursework includes physics, calculus, statistics, and programming.

How is climatology different from meteorology?

Meteorology focuses on short-term weather forecasting (days to weeks), while climatology studies long-term climate patterns (decades to centuries). Both study atmospheric processes but operate on different timescales. Meteorologists predict tomorrow's weather using real-time data; climatologists analyze historical datasets and use models to understand long-term global patterns.

What is the average salary for a climatologist?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (May 2023), environmental scientists and specialists (including climatologists) earned a median salary of $76,530. Federal positions typically pay more ($105,990 median). Entry-level positions start around $50,000-$60,000, while experienced PhD-level climatologists can earn over $100,000. The highest 10% earn more than $129,450 annually.

Where do climatologists work?

Climatologists work in federal agencies (NOAA, NASA, EPA), universities and research institutions, environmental consulting firms, state and local government, insurance and energy companies, and non-profit organizations. About 30% of environmental scientists work for federal government. Work environments vary by specialization-some involve extensive fieldwork, while others are primarily office-based computer modeling and data analysis.

What skills do I need to become a climatologist?

Essential technical skills include advanced mathematics, statistics, programming (Python, R, MATLAB), data analysis, atmospheric physics understanding, GIS, and research methodology. Important soft skills include scientific writing, communication abilities for explaining complex patterns to non-technical audiences, collaboration for interdisciplinary work, and critical thinking. Modern climatology increasingly requires machine learning and science communication capabilities.

Key Takeaways

- Diverse Career Opportunities: Climatology offers varied career paths in federal agencies, research institutions, consulting firms, and non-profits. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that environmental scientists and specialists (including climatologists) earn a median salary of $76,530, with federal positions exceeding $105,000 annually.

- Advanced Education Typically Required: Most climatology positions require at least a master's degree in atmospheric sciences or environmental science, with a PhD strongly preferred for research and academic roles. Strong foundations in mathematics, physics, statistics, and programming are essential starting in undergraduate studies.

- Growing Field with Steady Demand: The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 6% employment growth for environmental scientists and specialists through 2033, with approximately 7,000 annual job openings. Growth is driven by increased focus on climate change, environmental regulations, climate risk assessment, and adaptation planning.

- Distinct From Weather Forecasting: While meteorology focuses on short-term weather prediction, climatology examines long-term climate patterns, trends, and human impacts on global systems over decades and centuries. Both study the atmosphere but serve different purposes and use different analytical approaches.

- Interdisciplinary and Evolving: Modern climatology intersects with ecology, public health, economics, and social science. The field requires both traditional research skills and emerging capabilities in AI, machine learning, and science communication to address challenges in improving climate models, understanding societal impacts, and developing solutions.

Ready to explore environmental science programs that prepare you for a climate science career? Discover degree options that combine rigorous scientific training with the skills you'll need to address Earth's most pressing environmental challenges.

2024 US Bureau of Labor Statistics salary and job growth figures for Environmental Scientists and Specialists reflect national data, not school-specific information. Conditions in your area may vary. Data accessed January 2026.

Additional Resources

Related Environmental Science Careers:

- Park Ranger - Protect natural resources and educate visitors about conservation

- Solar Engineer - Design renewable energy solutions addressing climate change

- Environmental Health Professional - Study environmental impacts on public health

- Guide to Parasitology - November 19, 2018

- Desert Ecosystems: Types, Ecology, and Global Importance - November 19, 2018

- Conservation: History and Future - September 14, 2018

Related Articles

Featured Article

AI in Climate Science: Career Paths and Educational Opportunities