Archaeology is the study of human history through the examination of physical remains - artifacts, structures, landscapes, and technology left behind by past societies. It spans from prehistoric cultures to the modern era, using scientific excavation methods, theoretical frameworks, and emerging digital tools to reconstruct how people lived, worked, and thought.

If you've ever wondered how we know so much about civilizations that left no written records, the answer is archaeology. It's one of the few disciplines that lets us reconstruct the human story entirely from what people left behind - tools, buildings, garbage heaps, graves, and the landscapes they shaped. It began with antiquarian traditions stretching back to the Renaissance and even the Roman Empire, with modern archaeology taking shape around the late 17th and 18th centuries. Here's a comprehensive look at the discipline: where it started, how it works, and where it's headed.

Jump to Section

- What is Archaeology?

- Archaeology vs. Anthropology

- How Did Archaeology Start?

- Archaeological Theories

- Sub-Disciplines

- Future Threats & Challenges

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Key Takeaways

What is Archaeology?

Simply put, archaeology is the study of people in the past - their activities, cultural practices, tools, technological development, and, where possible, their beliefs and superstitions. It mostly looks at material remains but has evolved to examine landscapes and topography too, creating overlap with both human geography and environmental studies. The emergence of modern archaeology as a structured discipline took shape in Europe around the late 17th and 18th centuries, though the impulse to collect and interpret the human past is far older.

Today, professional archaeologists study both prehistoric and historic periods, though those who study the most distant past are more likely to be anthropologists than archaeologists. Archaeology also differs from paleontology, which studies fossils of extinct species rather than humans or human ancestors. The two disciplines do share methods and tools, and sometimes work on the same sites, especially where human remains are found alongside extinct species.

Learn more about becoming an archaeologist.

How Do Archaeology and Anthropology Differ?

That's not a simple question to answer, and it depends on where you live. In North America, archaeology is a subdivision of anthropology. In Europe, it works the other way around - and the main reason is that Europe has a far longer historic period. In the Americas, the prehistoric period is considered to have ended in the 15th and 16th centuries with the arrival of European colonists.

The two disciplines are remarkably similar in their tools and methods and complement each other in many ways. Academics from both would agree they've made wonderful contributions to each other and will continue to do so. But they do differ in key areas.

Anthropology is the study of people of the past: their culture and practices, habitation locations, how they survived in the landscape, what they ate, and what they believed. Anthropologists use this to build a narrative of human culture. If you're drawn to this side of things, an anthropology degree may be worth exploring.

Archaeology is the study of the material remains of the human past - artifacts like tools and jewelry, technology, buildings and structures, grave goods, and how humanity altered natural features and landscapes. Archaeologists study the physical things people left behind as indicators of the culture and practices that anthropologists study.

The similarities go beyond materials, though. Some archaeologists study modern culturally continuous groups to understand beliefs and practices of the past by studying their materials and technology. More details on this approach are in the subdisciplines section below.

How Did Archaeology Start?

Early Antiquarianism

Archaeology as a discipline grew from "antiquarianism" - a practice with roots stretching back to the Roman Empire and continuing through the Renaissance. The keeping of artifacts as cultural curiosities is an ancient impulse. Even in medieval societies, people collected images of ancient stone texts, sketches of curious monuments, and other objects we'd recognize today as archaeologically significant.

Later antiquarianism of the 17th and 18th centuries has its roots in the birth of the nation-state. This period saw fundamental changes across the European powers, with the idea of national cultural identity replacing a shared sense of Christian faith. It was also arguably the birth of genealogy. Famous English antiquarians like William Camden, Elias Ashmole, and William Dugdale had important roles for the crown in preserving the concept of royal lineage.

The Origins of Modern Archaeology

Modern archaeology grew from the Enlightenment, but it was still heavily influenced by national identity and local pride. It's no surprise that some of the world's best-known museums opened around this same period. The British Museum opened its doors in 1753. The Egyptian Museum of Antiquities opened in Cairo in 1835. The National Archaeological Museum of France was opened by Napoleon III in 1862.

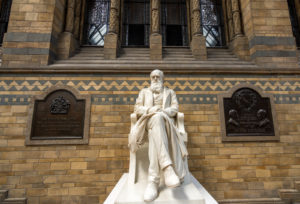

The shift from political curiosity-collecting to genuine scientific investigation accelerated dramatically with one publication: Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859. Darwin wasn't the first to propose evolutionary theory, but his work brought it into the mainstream - and it lit a fuse with profound effects on many sciences, including archaeology.

Evolutionary Theory Applied to Cultures and Artifacts

By the time Darwin published, archaeology was already looking at the evolution of culture and technology. Two Scandinavian antiquaries, Worsaae and Thomsen, had proposed the first "three-age" system for the relative dating of artifacts and their stratigraphic relationships - Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. These are simplistic designations, but we still largely use them today. Sir John Lubbock divided the Stone Age further into Paleolithic (old stone age), Mesolithic (middle stone age), and Neolithic (new stone age).

Darwin's work enabled many scientific disciplines to reexamine their foundational assumptions, and archaeology was no different. The old systems for understanding human antiquity were challenged at their core.

A Darwinian World, Through to the Modern Age

Archaeology was already in the middle of its own revolution when Darwin published. Stratigraphic theory was in development, partly building on the three-age system. William Cunnington excavated numerous prehistoric monuments across the Wiltshire landscape in the early 1800s - including sites at Stonehenge's surroundings - categorizing them using a meticulous system of stratigraphy that still informs archaeology today.

Archaeology was already in the middle of its own revolution when Darwin published. Stratigraphic theory was in development, partly building on the three-age system. William Cunnington excavated numerous prehistoric monuments across the Wiltshire landscape in the early 1800s - including sites at Stonehenge's surroundings - categorizing them using a meticulous system of stratigraphy that still informs archaeology today.

The first practitioner who truly looked like a modern archaeologist was General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, typically known as Pitt Rivers. He excavated on his land in England in the 1880s using methods considered meticulous by the standards of the day, arranging artifacts topologically by a presumed evolution of methods and complexity. It was arguably the first time archaeology examined artifact typology as a method for determining the relative evolution of their form.

But the most transformative figure in establishing modern archaeological methodology was William Flinders Petrie, widely regarded as a pioneer of modern archaeological methods. He was the first to systematically investigate the Great Pyramid of Giza, conducted extensive work in Memphis, and excavated widely throughout the Levant. In each case, he meticulously recorded every artifact - no matter how seemingly insignificant - its location, and its relationship with other finds and the surrounding landscape. This became the gold standard for archaeological practice.

Archaeology in the 20th Century

By the turn of the century, archaeology had become an academic discipline - no longer the hobby of Europe's elite. When Sir Mortimer Wheeler arrived on the scene in the early 20th century, the field underwent more transformation. He introduced the Wheeler-Kenyon Method of scientific excavation, developed with his student Kathleen Kenyon, which is still in use today. Before Wheeler, practitioners would smash through upper layers to reach what they considered "more interesting" material beneath - with little regard for a site's development, changing morphology, or cultural evolution. Wheeler finally removed the perception of archaeology as a treasure hunt.

By 1950, it was a professional academic discipline requiring high-level education. By the 21st century, the vast majority of professional archaeologists hold formal degrees - though avocational practitioners and field technicians in some contexts remain exceptions. The discipline now effectively has two sides: archaeology in theory, and archaeology in practice.

- Archaeology as a practice is the process by which archaeologists research sites, gather data, excavate, report on findings, and preserve artifacts. Tools range from excavation equipment to documentation research, aerial photography, cartography, soil sampling, palynology, and much more.

- Archaeological theory is the examination of those findings to extract meaning from artifacts, monuments, human landscapes, and other discoveries for knowledge dissemination and academic discussion.

Archaeological Theories

Archaeology isn't simply about digging up the past and putting it on display. Academic archaeology is about interpreting meaning - what objects and monuments tell us about what people thought, how they used things, who used them, and when. This is especially important for artifacts whose original meanings have been lost or where there are no written records to provide context.

Antiquarianism

The earliest theoretical stance of antiquarians and archaeologists was rooted in supernatural young-earth creationism - the expectation that all findings would fit a biblical framework. In the mid-17th century, the Archbishop of Armagh James Ussher examined biblical texts and deduced that the Earth was created in 4004 BC. This biblical dating dominated ideas about the past for generations.

The well-to-do of Europe were essentially treasure hunters, typically looking to prove a right to rule or find signs of existing class divisions in the ancient record. But what about mysterious artifacts they couldn't explain? Extinct creatures like mammoths and dinosaurs were worked into biblical chronology as giants and dragons from the Old Testament. Stone tools of ancient cultures were considered natural phenomena - probably the byproduct of storms.

Culture-Historical Archaeology

The 1860s saw a new movement emerge, fueled by Darwin's Evolutionary Theory and Charles Lyell's Uniformitarianism. Though deeply flawed in its acceptance of hierarchies, racial divisions, and class assumptions, it introduced genuine scientific investigation to the discipline for the first time. The three-age systems were applied with enthusiasm, and all cultures were seen as progressing linearly from barbarism to civilization.

Culture-Historical Archaeology's most enduring contribution was the concept of cultural migration and diffusion theory - the idea that ancient cultures could be categorized into homogeneous groups by geographic location and that technological ideas spread between them. It gave rise to several additional theoretical models:

- Historical Particularism argued the opposite of the linear model - that even neighboring cultures weren't necessarily influencing each other, and each culture's evolution had to be considered individually.

- National Archaeology used the ancient past to instill a sense of national or regional identity - the idea that a people were historically "special."

- Soviet Archaeology examined the social aspects of the past through a communistic lens, challenging the individualistic and class-based assumptions of earlier models.

Processual Archaeology (Also Known as New Archaeology)

Perhaps the USA's greatest contribution to archaeological theory, Processual Archaeology, is one of two major theoretical models still applied today. It began in the late 1950s, when American archaeologists argued that "American archaeology is anthropology, or it is nothing" - meaning both disciplines ultimately aim to discover and explain human society through the examination of different aspects of the past.

The core argument was that with a solid scientific method, archaeology could break free from the limitations of material remains and come to understand the actual lives of the people who interacted with those objects. It promoted cultural evolutionism and called for better quality data, championed by early pioneers like Colin Renfrew, Paul Bahn, and Lewis Binford. It was also the first theoretical framework in archaeology to examine environmental adaptation as an agent for societal change.

Post-Processualism

Post-processualism grew out of the limitations of processual archaeology's heavy positivism - its demand for quantifiable evidence for everything, including things that aren't easily quantifiable. Largely influenced by post-modernism of the 1970s, its major proponents were British archaeologists Ian Hodder, Michael Shanks, Christopher Tilley, and Daniel Miller.

Post-processualism aimed to put humanity back at the center of the discipline. It placed thoughts, feelings, spirituality, cultural behavior, ethics, and group and individual psychology at the heart of research. After all, humans don't always act rationally - superstition, imagination, and art are also core to human intellectual development, and those things don't always leave quantifiable data.

The main tensions between the two camps: processualism argues that you can't understand thoughts and feelings without physical evidence, and that objective conclusions are possible. Post-processualism argues that every archaeologist brings inherent bias to their interpretations - shaped by nationality, religion, political affiliation, ethnic identity, and age. In Europe, these movements are viewed as opposing. In North America, they're more often seen as complementary. In practice, most working archaeologists today draw on both frameworks - a hybrid approach formalized as Processual Plus, covered in the section below.

Processual Plus

Archaeology is now converging the two models. The science-based empiricism of processualism has its limits. The experiential focus of post-processualism sometimes overreaches into the unprovable. In the 21st century, Processual Plus looks for empirical evidence while also considering human psychology, group identity, gender, beliefs, cultural transmission, trade, and technological adoption. It allows for subjective interpretation of scientific data - accounting for hard evidence while applying a perception-based layer of understanding.

Archaeology Sub-Disciplines

Through the two major theoretical platforms, dozens of subdisciplines have emerged. Some focus on a specific aspect of the archaeological record, and others are defined by methodology. Here's a look at the main ones you'll encounter.

Through the two major theoretical platforms, dozens of subdisciplines have emerged. Some focus on a specific aspect of the archaeological record, and others are defined by methodology. Here's a look at the main ones you'll encounter.

Computational Archaeology

A relatively recent application, computational archaeology uses digital technology to perform complex data analyses that humans couldn't achieve individually. This includes Geographic Information Systems (GIS), surveying, and satellite data for spatial analysis, statistical modeling for big data analytics, intrasite analysis with 3D modeling, and predictive modeling for heritage conservation. It's also a powerful tool for sharing research within academia and with the public.

Environmental Archaeology

This broad subdiscipline examines human interaction with the natural world. It's divided into three main areas:

- Archaeozoology studies how humans interacted with animals in the past - ancient hunting practices, the transition to farming, and the distribution of animal species. Professionals here spend a lot of time on bone analysis and spatial modeling.

- Archaeobotany examines past human relationships with plants: ancient farming practices, land clearance, landscape changes, palynology, and phytoliths. There's also overlap with entomology since insect remains can serve as indicators of plant type change.

- Geoarchaeology looks at Earth-based data as it relates to the human past - palaeoclimate data from periods of human activity, broad distribution data of pottery and flint tools, and the spread of technological cultures across regions.

Ethnoarchaeology

With strong links to ethnography, this subdiscipline examines contemporary traditional societies - their beliefs, practices, hierarchies, technology, and social values - and uses that data to theorize about past human records. It has its limits: you can't assume that the practices of one contemporary traditional society explain why an entirely separate ancient culture did something similar. But it has helped resolve some long-standing archaeological mysteries. Seminal work in Alaska by Lewis Binford, for example, helped archaeologists understand the practices of paleolithic peoples in France and Germany.

Learn more about becoming an ethnoarchaeologist.

Experimental Archaeology

Don't let the name fool you - experimental archaeology is as rigorous as it is fascinating. The basic idea is to reconstruct the past by creating replicas of materials using only the methods available to the people being studied. That means working stone tools by hand, smelting early bronze and iron, constructing ancient buildings, and making period clothing. By testing theories about logistics, technology, and materials, experimental archaeology lets researchers verify what's actually physically possible - not just theorize about it. It's also made for compelling television, with several successful shows worldwide introducing the public to the discipline.

Feminist Archaeology

A subdiscipline of post-processual archaeology, feminist archaeology largely studies the role of women in past societies - their working roles, social status, and how gender was perceived and defined. But it also examines class, race, and sexuality. It's at the forefront of challenging older models that interpret ancient cultures through a modern Western lens. The assumption of male=hunter and female=homemaker in prehistoric societies, for example, has been repeatedly challenged through this approach. Many now refer to this area as "gender archaeology" since it incorporates the roles of all gender identities, not just women.

Forensic Archaeology

Forensic archaeologists specialize in the discovery and recording of human remains, and many work directly in criminology - examining recently deceased individuals for signs of crime. They're present at mass shooting sites, terrorist attack locations, and murder scenes. They're considered archaeologists because they use the same methods and tools used on historic sites. They don't just examine bodies either: environmental remains, soil samples, botanical data, and stratigraphy are all part of the toolkit. Their expert record is often what distinguishes a murder scene from a site of scientific or archaeological importance. For students drawn to this intersection of science and justice, there are dedicated forensic anthropology degree programs worth exploring.

Landscape Archaeology

Archaeology has always had a sense of historic landscapes and places, but for most of its history, it treated isolated monuments and relics as separate elements - not as part of a topographic or geographic network. Landscape archaeology fills that gap, treating the landscape itself as a historical record in its own right. It relies on new technologies referenced in computational archaeology above, as well as historic maps, land deeds, and accumulated survey and excavation data from past investigations. Many consider it both a technique and a theory.

Maritime Archaeology

Humans have always needed waterways - we mine their resources, travel on them, and build technology to use them. Maritime archaeology examines humanity's relationship with the sea: the evolution of rafts and boats, seafaring cultures like the Vikings, the spread of civilizations across island groups like Micronesia, and the archaeology of fishing. There's meaningful overlap with climate science, too. Some impressive prehistoric sites now lie beneath the world's seabeds on land that was once dry, and those submerged records are largely an untapped resource.

Urban Archaeology

A form of landscape archaeology, urban archaeology examines historic urban centers as a historical record. It focuses on why a site was chosen, its evolutionary development (expansion and contraction over time), the people who lived there, its industry, form, function, and wider strategic importance to the surrounding landscape. Towns and cities produce large stratigraphic records - historic remains are often preserved beneath layers of much later buildings. Urban archaeologists are particularly interested in what people threw away: trash, human waste, and discarded pottery and food all tell a rich story about everyday life in a historic urban center.

Future Threats and Challenges to Archaeology

Every generation of archaeologists faces its own unique pressures. The 21st century is no different - and in some ways, the challenges are more acute than ever before.

Climate Change

Climate change is one of the most serious threats the discipline has ever faced. Rising sea levels require greater coastal defenses to protect standing historic structures and buried remains, and coastal erosion is already damaging archaeologically sensitive sites. Changing topographies - whether from flooding, drought, or extreme weather events - threaten to destroy irreplaceable records before they can even be excavated or documented.

Political Instability

Political instability has always threatened cultural heritage, but modern conflict has brought it into sharp relief. Iconoclasm - the deliberate destruction of religious or cultural artifacts - is not new, but the scale of damage in the Middle East over recent decades has been catastrophic. The destruction of Buddhist statues in Afghanistan by Taliban fighters and the ancient Roman city of Palmyra by ISIS are among the most visible examples. Estimates from heritage organizations suggest tens of thousands of archaeological sites across the Middle East are under threat - a figure that has grown significantly with each new episode of regional conflict.

Tourism

Ironically, the one thing keeping many sites financially viable is also a threat to their survival. Land erosion at Machu Picchu has led to strict daily visitor limits. The Great Pyramids at Giza limit tomb access to only a few hundred people at a time - because the increased humidity and CO₂ produced by visitors has been shown by preservation studies to accelerate deterioration of wall surfaces and painted decoration inside the burial chambers. The Lascaux Cave in France has closed permanently to the public and is open only to researchers, while a near-flawless replica nearby handles tourist traffic.

Construction vs. Cultural Past

As the global population grows, so does demand for land - for housing, transportation, agriculture, and raw materials. International laws exist to protect archaeological remains, but they don't always hold in practice. In the developed world, archaeology frequently faces threats from development projects with money made available through developer funding. In the developing world, poor resources and weak regulation mean heritage protection is rarely a priority. The result is a discipline that's perpetually playing catch-up with construction timelines.

Cultural Sensitivity

Archaeology used to proceed with little concern for the cultural significance of what it was disturbing. That's changed significantly. Challenges from indigenous communities - particularly First Nations peoples in North America and Australian Aboriginals - have pushed the discipline toward co-operation with affected communities rather than treating their ancestors' remains as scientific data. This is now an important and ongoing conversation in the field.

Governmental Priorities

Heritage has always walked a financial tightrope. During periods of austerity, cultural budgets are often among the first to be cut, despite the widespread public value of archaeological sites and their potential to attract tourism and create jobs. For all but the globally famous sites, archaeology rarely generates revenue - and in fiscally tight times, governments around the world are trimming heritage budgets accordingly.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main purpose of archaeology?

Archaeology's main purpose is to understand human history through the physical remains people left behind. That includes artifacts, structures, landscapes, and environmental data. By studying these materials systematically, archaeologists reconstruct how people lived, what they believed, how they organized their societies, and how they changed over time - especially in periods and places with no written records.

How is archaeology different from anthropology?

Archaeology focuses on the material remains of the human past - physical objects, buildings, and landscapes. Anthropology focuses more broadly on human culture, behavior, and social structures, including living populations. In North America, archaeology is considered a subfield of anthropology. In Europe, the relationship is often reversed. The two disciplines share many methods and regularly inform each other's work.

How has archaeology changed over time?

Archaeology has transformed dramatically from its origins as an aristocratic treasure hunt. The introduction of stratigraphy in the 19th century brought scientific rigor. The Wheeler-Kenyon method in the early 20th century standardized excavation practice. The rise of processual and post-processual theory shifted the focus from simply cataloging objects to interpreting meaning. Today, computational tools like GIS, 3D modeling, and satellite imagery have revolutionized how sites are discovered, mapped, and analyzed.

What are the main subdisciplines of archaeology?

There are many, but the most widely practiced include: computational archaeology (digital data analysis and GIS), environmental archaeology (human relationships with animals, plants, and landscapes), ethnoarchaeology (studying contemporary traditional societies to understand the past), forensic archaeology (human remains and crime scenes), landscape archaeology (treating entire landscapes as historical records), and maritime and urban archaeology. Each uses distinct methods tailored to its subject matter.

What career paths does an archaeology background lead to?

An archaeology background can lead to careers as a field archaeologist, museum curator, heritage consultant, forensic specialist, environmental archaeologist, or academic researcher. Many professionals cross into related fields like anthropology, geographic information science, environmental science, and cultural resource management. Exploring an anthropology degree or the path to becoming an archaeologist are both good starting points.

Key Takeaways

- Archaeology studies the human past through physical evidence: Artifacts, structures, landscapes, and technology left behind by past societies form the foundation of archaeological knowledge - especially for cultures with no written records.

- It's distinct from but related to anthropology: In North America, archaeology is a subfield of anthropology. Both disciplines aim to understand human culture and history, but approach it from different angles - material remains vs. cultural practices.

- The discipline evolved dramatically over three centuries: From antiquarian treasure hunting rooted in the Renaissance to the scientific rigor introduced by figures like Pitt Rivers and Flinders Petrie, archaeology has transformed into a professional academic science with high methodological standards.

- Two major theoretical models frame modern interpretation: Processual archaeology emphasizes scientific empiricism and evidence-based interpretation. Post-processualism reintroduces subjectivity, human psychology, and cultural bias. Most modern practice blends both through Processual Plus.

- Archaeology faces serious 21st-century threats: Climate change, political instability, over-tourism, development pressure, and government budget cuts all pose significant risks to archaeological heritage worldwide.

Interested in turning your passion for the past into a career? Explore the degrees and programs that can get you there.

- What Is Parasitology? The Science of Parasites Explained - November 19, 2018

- Desert Ecosystems: Types, Ecology, and Global Importance - November 19, 2018

- Conservation: History and Future - September 14, 2018

Related Articles

Featured Article

How Hard Is Environmental Science? (What Current Students Wish They Knew)