Environmental science is moderately challenging-tougher than most social sciences but generally less demanding than engineering or pure chemistry. The real difficulty comes from juggling multiple science disciplines simultaneously, hidden math and chemistry requirements most students don't expect, intensive lab and fieldwork schedules, and the challenge of turning complex, messy environmental problems into clear data and analysis. Success depends more on steady effort and support-seeking than natural ability.

If you're researching environmental science programs, you've probably asked yourself: "Can I actually handle this major?" It's a fair question. Environmental science has a reputation for being challenging, but what does that really mean for you as a student?

The honest answer is nuanced. Environmental science sits in the moderate-to-challenging range of college majors. It's tougher than general studies or many social science degrees, but it's often less brutal than engineering, physics, or pure chemistry programs. However, that doesn't mean it's easy. Current students consistently say the difficulty isn't always about how hard individual concepts are-it's about the volume and variety of challenging work hitting you all at once.

Let's break down what makes environmental science challenging, what current students wish they'd known before starting, and how you can set yourself up for success. You might also want to explore whether environmental science is a good major as you consider your options.

Table of Contents

The Math Reality: How Much and How Hard?

Labs, Fieldwork, and the Real-Time Crunch

What Current Students Wish They'd Known

How It Compares to Other Majors

Can You Succeed in Environmental Science?

How Hard Is the Coursework?

Environmental science is inherently interdisciplinary. You're not just studying one science-you're studying several. Your typical course load might include biology, chemistry, geology, physics, and social science classes, often in the same semester. This means you're juggling multiple "intro weedout" sequences simultaneously while other majors are focused on just one or two core subjects.

When degree difficulty rankings compare majors, environmental science typically lands in the mid-range. It's consistently rated harder than business, communications, or social science programs, but it usually ranks below astrophysics, chemical engineering, and pure mathematics programs. This makes sense when you consider the breadth: you need scientific rigor across multiple disciplines, but you're not diving as deeply into the abstract theoretical work that makes some STEM majors brutally difficult.

Chemistry: The Make-or-Break Sequence

Ask any environmental science student what their toughest classes were, and chemistry-particularly general chemistry and organic chemistry-comes up repeatedly. These courses are common requirements and are often taken alongside pre-med students, which can drive up grading curves and increase competition. Many students report that these were their lowest grades and biggest sources of stress during their undergraduate years.

Here's the good news: upper-level environmental chemistry courses often feel more manageable. Why? They're applied. Instead of abstract exercises, you're using chemistry to understand real environmental problems-how pollutants move through ecosystems, how water treatment works, how soil contamination happens. When you can see the purpose behind the equations, the material becomes more intuitive.

Current students' advice on chemistry is consistent: don't try to cram. Treat it like learning a language-lots of small, frequent practice sessions work better than marathon study sessions before exams. Use tutoring centers, form study groups, and don't wait until you're failing to ask for help.

How Program Type Affects Difficulty

Not all environmental science programs are created equal, and this significantly affects how hard your degree will feel. Some programs lean heavily into quantitative science-think hydrology, geochemistry, and environmental modeling with lots of calculus and physics. Others emphasize policy, sustainability planning, and qualitative research methods.

Online discussions among environmental science students vary widely by school. Students in science-intensive programs report experiences similar to those of traditional lab science majors. Students at policy-focused programs describe something closer to a social science major with some science requirements. Neither approach is better, but they're dramatically different experiences.

The consensus among current students is that if you can pass introductory chemistry, enjoy being outdoors, and are willing to study steadily, the major is demanding but doable. The students who struggle most are those caught off-guard by requirements they didn't expect.

The Math Reality: How Much and How Hard?

Here's where environmental science gets tricky. Environmental science is sometimes marketed in recruitment materials as "a science degree for people who aren't great at math." This is misleading. While you won't need as much advanced mathematics as an engineering major, you'll still need solid quantitative skills.

Typical Math Requirements by Program Type

Math requirements vary significantly between programs:

At a minimum, you'll need college algebra and statistics. This is common for environmental studies or policy-focused tracks. If you're comfortable with high school algebra and willing to learn basic statistical concepts, this level is manageable for most students.

Many BS programs in environmental science require Calculus I and II, plus statistics. This is where many students start to feel challenged, especially if math wasn't their strongest subject in high school. According to student experiences shared in online forums, calculus II is often cited as especially challenging.

Science-intensive programs may require calculus I through III, plus statistics and possibly differential equations. This approaches the math load of engineering or physics programs. These programs are usually clearly labeled as quantitative or designed for graduate school preparation.

What Current Students Say About Math

The experiences of current students vary widely. Some report "I only needed algebra and statistics, and I'm average at math-I did fine." Others say, "I had to take calc I through III plus statistics, and it was challenging but survivable." The jump to calculus can intimidate many students, but with tutoring centers, office hours, and study groups, most who put in consistent effort can pass.

An important insight from upper-level students: while advanced calculus is rarely used in day-to-day work in many environmental jobs, statistics and basic quantitative reasoning are essential. Data analysis, GIS work, and research all require comfort with numbers. If you're going into environmental science, you'll need to make peace with quantitative thinking, even if you're not naturally "a math person."

Here's what helps: applied mathematics in environmental contexts often feels easier than standalone math classes. When you're using statistics to analyze species population data or using calculus to model pollutant dispersion, the math has a clear purpose. Many students report that environmental modeling or ecology classes made math concepts click in ways that abstract math classes never did.

Surviving the Math Requirements

Current students emphasize that persistence matters more than natural ability. You don't need to be a math prodigy. You do need to:

Show up to office hours when you're confused (not after you've failed two exams). Form study groups with classmates. Use your university's tutoring center from week one, not week ten. Practice problems consistently instead of cramming before exams. Connect the math to real environmental applications whenever possible.

If you're reading this in high school or community college, shore up your algebra skills now. Make sure you're comfortable with logarithms, exponentials, and graphing. This foundation makes calculus and statistics dramatically easier later.

Labs, Fieldwork, and the Real-Time Crunch

Even when individual classes aren't conceptually extreme, the time demands make environmental science feel hard. This is something prospective students often underestimate.

The Lab Component

Lab courses aren't just longer classes-they're different beasts entirely. A typical lab might require a three-hour block where you're collecting data, running experiments, and working with equipment. Then you go home and spend another three to five hours writing up the lab report, analyzing data, and answering questions.

If you're taking two or three lab courses in one semester (not uncommon for environmental science majors), you might have 15-20 hours of lab work per week on top of regular coursework. Factor in group lab work, where you're coordinating schedules with partners, and the time commitment becomes significant.

Here's what surprises students: the reports. Labs aren't just about showing up. The detailed write-ups, data analysis, and research require strong writing skills and careful attention to methods. If you're not naturally organized, labs will force you to develop those skills quickly.

Fieldwork Demands

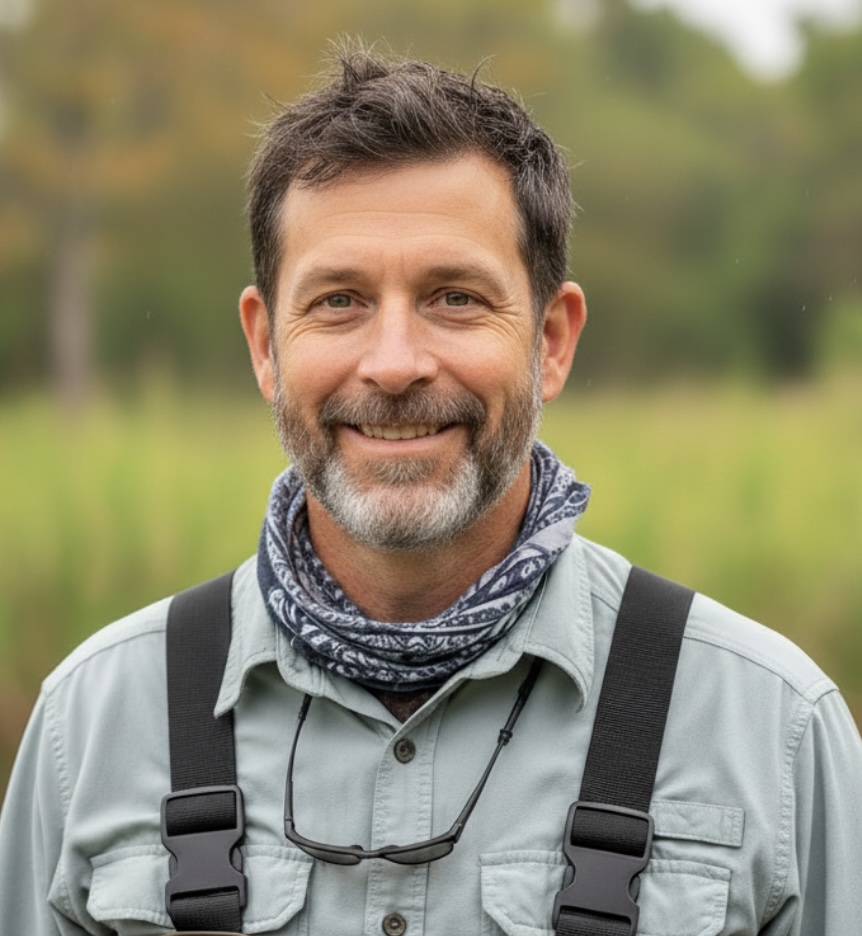

Field methods courses add an entirely different dimension. You might have 6 a.m. bird surveys, weekend trips to collect water samples, or all-day sessions in the field, regardless of the weather. This is often the most fun part of the major-you're outside, doing real science, getting hands-on experience. But it's also exhausting.

Field days are long. You might spend eight hours collecting soil samples, then come back and spend another few hours processing and labeling them. Some programs require multi-day field trips, which means you'll need to manage coursework from other classes while you're away from campus.

Current students love fieldwork, but they also warn that it can overload your schedule if you're not careful. Taking a field methods course, two lab sciences, and a demanding non-science course in the same semester is a recipe for burnout.

The Internship and Research Expectation

Many environmental science programs expect or strongly encourage internships, independent research projects, or an honors thesis. This is excellent preparation for careers and graduate school, but it adds another layer of time commitment.

Research projects mean you're doing real data collection and analysis on top of your classes. You might spend 5-10 hours per week in a professor's lab, processing samples, entering data, or writing code. Internships often require 10-20 hours per week during the semester or a full-time commitment over the summer.

Students describe the emotional and logistical load of group projects as particularly challenging. Coordinating fieldwork with classmates, sharing datasets, dealing with uneven effort in teams-these "soft skills" challenges can make semesters with multiple project-heavy classes especially exhausting.

Some universities use compressed or 8-week sessions for certain courses. Students report that these make classes feel more intense because the same content is squeezed into half the time.

What Current Students Wish They'd Known

After reviewing discussions in online student communities like Reddit-where environmental science students share recurring concerns about their experiences-and examining insights from what students wish they'd known before majoring in environmental science, several themes emerge consistently. Here's what current students wish someone had told them before they committed to the major.

It's More Quantitative Than the Brochure Suggests

Marketing materials for environmental science programs often emphasize the "save the planet" mission and outdoor fieldwork. They're less enthusiastic about advertising the chemistry, physics, and statistics requirements. This leads to a gap between expectations and reality.

Students wish they'd realized sooner that environmental science degrees involve real, challenging quantitative work. It's not just discussions about conservation-it's calculating pollutant loads, analyzing water chemistry data, modeling population dynamics, and using statistical software.

The advice from upper-level students to incoming students: shore up your algebra and basic chemistry skills in high school or community college. Take science seriously from day one. Expect at least one genuinely difficult math or chemistry course every year of your program. If you go in expecting a "soft science" major, you'll be blindsided.

That said, you don't need to be a math prodigy. You do need to be willing to practice, seek help early, and develop comfort with quantitative thinking. Students emphasize that persistence and good study habits matter more than natural ability.

Chemistry Can Be the Toughest Hurdle

General chemistry and organic chemistry deserve their own category because they're so frequently cited as the make-or-break courses. Many students report that these were their lowest grades across four years of college.

The students who succeeded developed consistent weekly problem-solving routines rather than cramming before exams. They used office hours, formed study groups, and treated chemistry like a skill to practice daily rather than content to memorize.

Here's something else students wish they'd known: if the heavy-science version of environmental science isn't working for them, many universities offer alternative tracks. Environmental studies, environmental policy, or sustainability programs offer ways to address environmental issues without the full chemistry load. Some students switch to these tracks after struggling with science prerequisites and report being much happier. This isn't giving up-it's finding the right fit.

The Interdisciplinary Load Is Mentally Tiring

The variety of environmental science is part of what makes it interesting. It's also what makes it exhausting. In a single week, you might be writing biology lab reports, completing quantitative geology problem sets, reading policy case studies, and working on a GIS mapping project. Each requires a different type of thinking.

Students say this interdisciplinary juggling is what makes the major feel overwhelming, even when individual assignments aren't that hard. Your brain is constantly switching between different subjects, methods, and vocabularies. It's cognitively demanding in a way that majors with a stronger focus (such as pure chemistry or economics) aren't.

Time management becomes critical. Students wish they'd developed stronger organizational habits earlier-using planners, blocking off specific hours for lab reports, and setting aside time for the slow work of data analysis and scientific writing. They also recommend not stacking too many lab sciences in a single semester. If you can spread them out across your four years, do it.

Upperclass students often advise building in at least one lighter or gen-ed class each semester. This protects mental health, provides balance, and leaves time for internships and job applications. Learning to say no to extra clubs or unpaid opportunities isn't failure-it's essential for managing the workload.

Technical Skills Matter as Much as Grades

GIS, coding (particularly R and Python), and applied statistics are the skills that actually open doors in environmental careers. Many internships and entry-level jobs explicitly require GIS experience or data analysis capabilities. Yet students often don't realize this until junior or senior year, when they start applying for jobs and see what employers actually want.

Students wish they'd prioritized courses that teach these technical skills earlier. Even if a GIS class or a coding-intensive research methods course seems "extra hard" at the time, it pays off substantially. Employers care less about whether you got an A in every ecology lecture and more about whether you can clean messy datasets, create informative maps, and write clear technical reports.

The advice: treat any course that teaches GIS, remote sensing, R, Python, or advanced statistics as a priority. Join a professor's research project even if it's just a few hours per week-the hands-on technical experience matters more than adding another easy elective to pad your GPA. Look for environmental science internships that emphasize hands-on technical work, even if they're challenging.

The Emotional Side Is Real

This one catches students off guard. Many environmental science students chose the major because they care deeply about environmental issues. Then they spend four years studying climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and ecosystem collapse. Reading grim scientific projections semester after semester takes an emotional toll.

Students report experiencing "eco-anxiety"-a sense of dread or helplessness about environmental problems. Some semesters feel discouraging, especially when the news cycle reinforces the problems you're studying in class. Students wish someone had warned them that this is normal and that it's okay to feel overwhelmed sometimes.

What helps: staying connected to hopeful, solutions-oriented work. Volunteer with local restoration groups. Work on campus sustainability projects. Join research that directly informs conservation or clean energy policy. These activities remind you that the work matters and that positive change is possible.

Equally important: talk openly about stress. Don't try to carry the emotional weight alone. Classmates understand what you're going through. Advisors can point you to resources. Counselors can help with anxiety management. The students who struggle most are those who try to tough it out silently.

How It Compares to Other Majors

Context helps. Here's how environmental science typically compares to other STEM and science-adjacent majors:

| Aspect | Environmental Science | Traditional Lab Sciences (Chemistry/Biology) | Engineering (Civil/Chemical/Environmental) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Difficulty | Moderate to high; interdisciplinary load and labs are the main challenge | High; very intensive sequences in chemistry, physics, and often organic chemistry | Very high; heavy calculus, physics, and design courses every semester |

| Math Level | Algebra through calculus I-II and statistics; heavier at science-oriented schools | Similar or slightly more math than environmental science at many schools | Calculus I-III, differential equations, advanced modeling |

| Time Demands | Labs, field trips, group projects; significant outside-class work | Labs and problem sets; fewer field days but more intensive lab sequences | Very large problem sets, labs, and design projects; extensive time commitment |

| Content Focus | A mix of ecology, earth science, chemistry, policy, GIS, and statistics | Deep dive into one science (chemistry or biology) plus supporting courses | Applied math, physics, and design of infrastructure and systems |

| Perceived "Hardness" | Often called challenging but manageable with steady effort | Frequently described as one of the hardest STEM routes | Commonly ranked among the toughest undergraduate degrees |

Environmental science sits in an interesting middle ground. You're not going as deep into any single subject as a pure chemistry or biology major, but you're covering more breadth. You're doing real quantitative work, but usually not at the level of mathematics required for engineering. The challenge is integration-bringing multiple perspectives together to address complex environmental problems.

Can You Succeed in Environmental Science?

Let's reframe the question. Instead of asking "Am I smart enough for environmental science?", ask "Am I willing to work steadily and seek help when I need it?"

Who Tends to Thrive

Students who succeed in environmental science share some common characteristics, but natural genius isn't one of them. Here's what actually predicts success:

Genuine interest in environmental issues. This sounds obvious, but it matters enormously. When you care about why pollutant transport modeling matters for water quality, or why population dynamics matter for conservation, you're motivated to push through difficult problem sets. Passion doesn't replace hard work, but it fuels persistence.

Willingness to seek help early. The students who struggle most are those who wait until they're failing to ask for help. Successful students use office hours, form study groups, and visit tutoring centers starting in the first weeks of difficult classes. They're not embarrassed to say, "I don't understand this."

Comfort witha slow, sometimes frustrating scientific process. Real environmental science involves messy data, field days when nothing works right, and analyses that take weeks. If you need immediate results and clear answers, you might find the major frustrating. If you can tolerate ambiguity and incremental progress, you'll be fine.

Basic quantitative skills or willingness to develop them. You don't need to love math, but you can't run from it. Students who succeed either come in with decent algebra skills or commit to building those skills through tutoring and practice.

Practical Tips Before You Commit

If you're considering environmental science, do this research before you enroll:

Check your specific university's sample degree plan. Look at exactly which math and chemistry courses are required. Search for the syllabi online to see what topics are covered. This removes surprises.

Look at the program's focus. Does it lean toward the law or science? Are there multiple tracks (quantitative vs. qualitative)? Some schools let you choose a chemistry-light path. Others require the full lab science sequence for everyone.

Space out lab-heavy classes if you can. Don't take three lab courses plus a field methods course in one semester if you have any choice. Your future self will thank you.

Prioritize at least one GIS or statistics-heavy course per year. Front-load technical skills rather than saving them all for senior year. The earlier you learn GIS and coding, the more opportunities open up for research and internships.

Build support systems from day one. Find study partners in your intro courses. Introduce yourself to professors. Learn where the tutoring center is. These relationships matter more than you think.

When Environmental Studies Might Be a Better Fit

Environmental science isn't the only way to work on environmental issues. If you're passionate about conservation, sustainability, or climate action but genuinely struggle with chemistry or math, consider environmental studies, environmental policy, or sustainability programs.

These programs address environmental problems through social science, policy analysis, communications, and advocacy rather than lab science. They're not "easier" in terms of overall rigor-they emphasize different skills. You'll write more, read more policy documents, and focus on the human dimensions of environmental issues.

Some students start in environmental science, realize it's not the right fit, and switch to environmental studies. They often report being much happier because they're playing to their strengths. You can always add technical skills later through electives, online courses, or graduate school if you decide you need them.

The goal is finding the right path for your interests and abilities, not proving you can survive the hardest possible version of the major.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do you need to be good at math for environmental science?

You don't need to be a math prodigy, but you do need at least moderate math skills and a willingness to learn. Most programs require algebra through calculus I or II, plus statistics. If you're anxious about math, start by assessing what your specific program requires-some are much more math-intensive than others. Use tutoring centers, office hours, and study groups from the beginning of any math course. The students who succeed aren't necessarily naturally talented at math; they're the ones who practice consistently and ask for help early.

Is environmental science harder than biology?

It depends on the program, but generally, environmental science is either comparable to or slightly easier than a traditional biology major. Biology majors typically take more intensive science sequences (organic chemistry, genetics, molecular biology) and go deeper into biological systems. Environmental science is broader-you're touching multiple sciences but not going as deep into any single one. However, the interdisciplinary nature of environmental science creates its own challenge: you're juggling multiple types of coursework simultaneously. Some students find biology's focus easier; others preferthe variety of environmental science.

What's the hardest part of an environmental science degree?

According to current students, the hardest parts are usually the chemistry sequence (especially general and organic chemistry), the time crunch of juggling multiple labs and fieldwork, and the mental load of constantly switching between subjects (biology, geology, policy, statistics). Individual experiences vary-some students find chemistry manageable but struggle with calculus, while others breeze through math but find lab reports tedious. Most students agree that time management and the interdisciplinary juggling act are the universal challenges.

Can I major in environmental science if I struggled with chemistry?

Yes, but you'll need to be strategic. First, assess your program's requirements-some environmental science tracks require less chemistry than others. Second, consider whether you struggled with chemistry because of poor teaching, lack of effort, or genuine difficulty with the concepts. If it were teaching or effort, you might do fine with a fresh start and better study habits. If chemistry concepts fundamentally don't click for you despite effort, consider environmental studies or policy tracks instead. You can also look at programs that let you substitute some chemistry requirements with other sciences. Talk to academic advisors at programs you're considering about flexibility.

How much time do environmental science majors spend on homework?

This varies enormously by semester and course load, but expect 15-25 hours per week outside of class time for a typical full-time course load (12-15 credits). Lab courses add significant time-each lab might require 3-5 hours of out-of-class work for write-ups and data analysis. Field-intensive semesters might have weekend commitments. The workload tends to be heavier than that of social science or business majors but comparable to that of other lab science majors. The time crunch gets worse if you're also working a job, playing a sport, or heavily involved in extracurriculars. Students who manage their workload best use time blocking, set aside specific hours for lab work, and avoid procrastination on long-term projects.

Key Takeaways

- Environmental science is moderately difficult and manageable: it's tougher than the social sciences but generally less intense than engineering or pure chemistry. Success depends more on consistent effort and seeking help than natural ability.

- Math and chemistry requirements surprise many students: most programs require at least Calculus I-II and statistics, plus general chemistry and, often, organic chemistry. Check specific program requirements before committing, and build strong algebra skills in high school or community college.

- The real challenge is juggling multiple disciplines: you'll regularly switch between biology, chemistry, geology, policy, and statistics. This interdisciplinary load requires excellent time management and organizational skills more than genius-level intelligence.

- Technical skills open more doors than grades alone: Employers value GIS, coding (R/Python), and data analysis experience. Prioritize courses and research opportunities that build these skills, even if they're challenging. Join a professor's research project early.

- The emotional toll of studying environmental problems is real: Eco-anxiety and burnout are common. Stay connected to solutions-oriented work, talk openly about stress with classmates and counselors, and remember that caring about the environment is why you're here-it's a strength, not a weakness.

Ready to explore environmental science programs that match your interests and abilities? Browse accredited environmental science degree programs to find the right fit for your goals. Whether you're drawn to fieldwork, lab research, policy analysis, or conservation, there's a path in environmental science for you.

Related Articles

Featured Article

Zoology: Exploring the Animal Kingdom as Academic Pursuit