Climate change threatens more than half of North American bird species with significant population declines through disrupted breeding cycles, shrinking habitats, and range shifts. Rising temperatures cause phenology mismatches where birds arrive too late for peak food availability, contributing to reproductive declines of up to 90% in some migratory populations, such as the pied flycatcher. Coastal habitat loss, coral reef degradation, and wetland disappearance compound these threats, while solutions focus on habitat protection, restoration, and addressing greenhouse gas emissions.

Birds have been a prominent feature of life on Earth for eons. The adaptations commonly associated with this group of animals, such as feathers, hollow bones, and air sacs, evolved in piecemeal fashion almost as soon as dinosaurs arose, more than 230 million years ago.1 Present-day birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs, a lineage that includes Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor. Around 150 million years ago, during the late Jurassic, Archaeopteryx, considered a transitional form between dinosaurs and birds, first took to the skies.1 This opened up a vacant niche for these animal,s and evolution advanced rapidly, eventually giving rise to the 10,000 known bird species living today.

Despite this ancient history, birds today face an increasing number of threats to their existence, especially from anthropogenic climate change. While some of these seem relatively minor, experts predict that climate change could send more than half of the bird species in North America to join their ancestors in extinction.2 A thorough understanding of the ways in which climate change can impact birds is essential in predicting extinction risk and in developing possible mitigation strategies.

Jump to Section

- Climate Change

- Phenology

- Range & Distribution

- Habitat Destruction

- Invasions and Outbreaks

- Climate Change Impacts on Birds: Summary by Category

- Consequences

- Solutions

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Key Takeaways

Climate Change

To assess how climate change will affect birds, it is prudent to first examine how the planet is changing. Climate change is predominantly driven by increases in greenhouse gas emissions, such as carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were approximately 280 ppm. Today's levels have increased by approximately 50% to 420 ppm.3 This level is greater than at any point in the last 800,000 years; some estimates suggest up to 3 million years.4 In addition to this increase in magnitude, the current rate of increase is at least 10-100 times faster than natural post-glacial increases over the last 800,000 years.5

These greenhouse gas emissions have resulted in a global temperature increase of approximately 2�F since pre-industrial times, with two-thirds of that increase occurring over the last several decades at an accelerating rate. Temperatures in the Arctic have increased more than twice as much as those of the rest of the planet.6. Average global temperatures are expected to continue rising significantly by the end of the century without substantial emissions reductions.

An obvious consequence of this warming is a hotter climate in many regions of the globe. Climate change will also lead to prolonged droughts and wildfires in many arid regions, including the southwestern United States. Tropical regions will see an increase in the intensity and frequency of hurricanes. This will result in flooding and damage from high winds. Sea level is projected to rise as glaciers melt, eroding beaches and coasts. As the ocean warms, it will also become more acidic as it absorbs an increasing amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide. These changes will dramatically change many habitats, with important consequences for the birds that rely on them for survival.6

Phenology

Climate change has already been documented to affect the phenology, or timing, of birds' natural events. Because temperatures serve as triggers for many species to undertake important events such as migration or reproduction, shifts in temperature can alter the timing of these activities.

A good example of how this can impact birds comes from a long-term study of great tits (Parus major) in Europe.7 These birds time reproduction to when prey will be most abundant for nestlings, as those raised during peak prey abundance are heavier and have increased survival rates. Their main prey consists of caterpillars in oak trees, which emerge during tree bud burst in the spring, before pupating in the soil. This leaves a narrow window in which to time reproduction to coincide with peaks in prey abundance. To accomplish this, birds use temperature as a cue to initiate reproduction.

These problems are intensified in migratory species. Pied flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca) have been studied in the same habitat as the aforementioned great tits.8 These birds are different in that they overwinter in tropical Africa before migrating to Europe in the spring to breed. They use day-length variation in their wintering grounds as a cue for migration, which is not based on temperature. Because prey availability is temperature-dependent, it has started earlier in the year, resulting in birds not arriving at breeding grounds in time to take advantage of peak prey. This represents a mismatch in cues because migrations are independent of temperature; thus, birds cannot alter migration patterns as the climate changes. As a result, reproductive output has dropped, and local populations have declined by up to 90% in some studied areas due to phenological mismatch.8 Those populations with the earliest food peaks have had the largest declines, indicating that decreased prey availability is a major factor in these declines.

Range & Distribution

As the planet warms, habitats will shift, potentially reducing the ranges of many species. Rare species that are adapted to very specific habitats, such as those at the tops of mountains, are projected to be the most at risk. Species at the poles are very susceptible as well. The ranges of boreal birds in Northern Europe are predicted to decrease by more than 73% over the next century.9 Birds in more tropical regions may be able to expand their range as temperatures rise, but birds in northern Europe are blocked from northward expansion by the Arctic Ocean. The impacts of climate change on bird ranges are not uniform but will likely vary across latitudes and depend on ecological requirements.

Habitat Destruction

While some species will experience range contraction, others will face habitat loss from climate change. These threats take many forms across different ecosystems, from coastal areas to tropical reefs to inland wetlands.

Coastal Habitat Loss

Many birds in North America stopover in intertidal mud flats during their migrations, where they forage on invertebrates. Sea-level rise is projected to cause the loss of up to 70% of this habitat in some locations, jeopardizing the survival of these birds.10 Many birds that inhabit coastal areas, such as piping plovers (Charadrius melodus), lay their eggs directly on the sand of the beach in a shallow depression.11 The erosion of beaches from sea level rise will decrease the availability of this nesting habitat. Larger storm surges will also cause nests to be lost to the ocean.

Coral Reef Degradation

Birds that rely on coral reefs will face similar challenges. About one-third of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is taken up by the ocean, which makes the water more acidic. Increased acidity inhibits the ability of corals to secrete calcium carbonate, which forms the structure of the reef. As a result, they become brittle and prone to breaking.12 Decreased skeletal density and shrinkages in reef structure have been documented in many oceans.13 For many birds in the tropics, coral reefs provide an important food source and are critical habitats for their survival. The degradation of coral reefs due to climate change poses serious risks to these birds.

Prairie Wetland Loss

The prairie region of the Great Plains provides another important example of potential habitat loss. This region is covered with millions of glacially formed lakes that comprise one of the most productive habitats for waterfowl in North America, producing more than half of the ducks on the continent.14 Increasing temperatures and decreasing precipitation will lead to many of these wetlands drying out. Birds may have to shift from the more productive wetlands in the center of the region to those located on the fringes, where wetlands are less productive, and many have been drained for agricultural use.

Invasions and Outbreaks

Climate change may also facilitate the range expansion of invasive species, many of which are inhibited in their ranges by temperatures. The hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) is an insect introduced from Japan that has caused widespread mortality of hemlock trees across the Eastern United States.15 Winter temperatures prohibit the northward expansion of this pest, and have insulated some forests from its devastation. As temperatures warm, however, the pest may spread into new forests, causing further damage.

Similarly, invasive plants such as glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus) and Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) may spread into new forest regions as rising temperatures lift inhibitions to range expansion. These plants are detrimental to forests because they reduce the recruitment of canopy-forming trees and can damage existing trees. In addition to range contractions, many species will also have to contend with invasive species expansions, which will make the remaining habitat less suitable.

The health of many bird populations may also be affected by disease outbreaks. In Hawaii, mosquitoes that carry malaria are limited by temperature changes along altitude gradients.16 This means that malaria outbreaks are more common at lower altitudes, but higher areas on mountaintops create a refuge for birds because mosquitoes cannot reach the area. Increasing temperatures have led mosquitoes to move farther up mountain slopes, threatening birds that live at the mountain's summit. Avian malaria is thought to be a major cause in the decline of endemic Hawaiian birds, so its spread is sure to have a strong negative effect on bird populations.

Climate Change Impacts on Birds: Summary by Category

| Impact Category | Mechanism | Example Species | Documented Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenology Mismatch | Temperature cues shift breeding/migration timing out of sync with food availability | Pied Flycatcher, Great Tit | Up to 90% population decline in some studied areas |

| Range Contraction | Warming temperatures reduce suitable habitat, particularly at high latitudes | Boreal forest birds, Arctic species | 73% projected range decrease for northern European birds |

| Coastal Habitat Loss | Sea level rise erodes beaches and intertidal zones used for nesting and foraging | Piping Plover, shorebirds | Up to 70% loss of critical stopover habitat |

| Ecosystem Degradation | Ocean acidification and warming damage coral reefs; drought dries wetlands | Tropical seabirds, waterfowl | Loss of feeding grounds and breeding habitat |

| Disease & Invasives | Warmer temperatures allow pests, pathogens, and invasive species to expand ranges | Hawaiian honeycreepers | Avian malaria spreading to higher elevations, threatening refugia |

Consequences

The long-term impacts of climate change on birds remain poorly understood. Many species will face extinction. The consequences of climate change are even more complex when combined with other anthropogenic threats.

Compounding Anthropogenic Threats

For example, the cerulean warbler (Setophaga cerulean) spends winters in the Andes and then migrates to the Appalachian Mountains to breed. Its range has already been restricted from development for coffee plantations in its winter grounds and coal mining in its breeding grounds.2 These prior habitat alterations make it even more susceptible to declines from climate change.

Birds in tropical rainforests have been shown to not cross clearings for roads because they do not want to leave the shelter of the canopy.17 In places where the habitat has already been fragmented by roads, birds may be hesitant to cross them, which could hamper their ability to move into new habitats.

In many cases, there will also likely be interactions with native species when a bird expands its range. For example, ospreys are projected to lose up to 68% of their summer range and may become a year-round resident of Florida.2 American white pelicans may expand their coastal range by up to 89%, according to modeling projections.2 These birds may be a source of food competition with birds already in the area, which could put additional stressors on them. They may also overexploit prey, triggering trophic cascades that affect the entire ecosystem. Ospreys have also been documented eating other birds, so they may pose a threat to birds in the area, particularly if fish become scarce. There will likely be complex system-wide interactions as birds expand their ranges.

Ecosystem Service and Economic Impacts

The loss of many bird species would result in the loss of the ecosystem services they provide, many of which will become increasingly important as the planet warms. For example, salt marshes serve as a buffer from storm surge, preventing coastal erosion. Birds that inhabit these areas contribute to marsh health by aiding in nutrient cycling.18 Without birds, marshes will deteriorate and not be as effective in protecting against floods as coastal areas face more and more storms.

Loss of waterfowl from the productive wetlands of the Great Plains would eliminate them as a recreation source for hunters, as well as the revenue hunting permits provide to governmental agencies. There would also be significant cultural impacts from bird losses. The bald eagle, which is iconic to the United States and factors heavily in many Native American religions, may lose up to 75% of its current summer range by 2080 under high-emissions scenarios.2 These cultural losses may not have tangible consequences, but would certainly be lamented by most people. It would also rob future generations of the opportunity to view these birds in the wild.

Solutions

The most obvious solution to these issues would be to stop climate change, but this is extremely complicated, both economically and politically. Additionally, even if we stopped emitting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, continued warming would result from those already emitted.2 Birds will certainly have to contend with a warmer planet in the coming years.

Habitat restoration and protection are important for many bird species. As forests in Northern Europe shrink, establishing refuges that do not endanger birds will maximize the habitat available to them.9 In particular, preserving large expanses of contiguous habitat will be essential for conservation. In the Great Plains, many wetlands have been converted to agricultural fields. Restoring them to their prior state would increase habitat for waterfowl and enable some degree of resilience against climate change.14 Constructing artificial nesting sites may also lead to higher reproductive output and population growth for some species.19

Successful conservation strategies will rely on continued data collection to fully understand the impacts of climate change on birds and on prioritizing habitats and populations that give species the best chance of survival. Professionals in fields like wildlife biology, ornithology, and zoology play critical roles in monitoring bird populations, conducting research, and implementing conservation measures. Those interested in contributing to these efforts can pursue education in fish and wildlife management, conservation biology, or related environmental science disciplines.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many bird species are threatened by climate change?

More than half of North American bird species face significant threats from climate change, with experts predicting potential extinction for many if current warming trends continue. The impacts vary by species and region, with birds in polar regions, high mountain habitats, and coastal areas facing particularly severe risks. Some populations have already experienced declines of 90% or more due to climate-related habitat changes.

What is phenology and why does it matter for birds?

Phenology refers to the timing of natural events, such as migration, breeding, and prey emergence. Birds rely on environmental cues, such as temperature, to time these critical life events. Climate change disrupts these cues, causing mismatches where birds arrive at breeding grounds after peak food availability has passed. This phenological mismatch reduces reproductive success and can lead to significant population declines, as documented in species such as the pied flycatcher.

Can birds adapt to climate change quickly enough?

Most bird species cannot adapt rapidly enough to keep pace with current climate change rates, which are occurring 10-100 times faster than natural post-glacial increases. While some species may adjust breeding timing or shift ranges, these adaptations often lag behind environmental changes. Migratory birds face particular challenges because their migration timing is controlled by day length in wintering areas rather than temperature, making it difficult to synchronize with temperature-dependent food availability in breeding areas.

Which bird species are most at risk from climate change?

Birds at greatest risk include those in polar and boreal regions (facing 73% range reductions), high-elevation species with nowhere left to move as temperatures rise, coastal nesters like piping plovers threatened by sea level rise, and tropical reef-dependent species facing coral degradation. Species with restricted ranges, specific habitat requirements, or those already impacted by human development face compounded threats. The bald eagle may lose up to 75% of its current summer range by 2080 under high-emissions scenarios.

What can individuals do to help birds affected by climate change?

Individuals can support bird conservation through habitat protection, participation in citizen science projects that monitor bird populations, reduction of personal carbon footprints, and support for policies that address climate change. Creating bird-friendly spaces with native plants, reducing pesticide use, and preventing collisions with windows also help. Those interested in professional conservation work can pursue careers in wildlife biology, ornithology, or environmental science, where they can contribute to research and conservation strategies that give bird species the best chance of survival.

Key Takeaways

- Phenology Disruption: Temperature shifts cause critical timing mismatches between bird breeding cycles and peak food availability, contributing to reproductive declines of up to 90% in some migratory populations, such as pied flycatchers.

- Widespread Habitat Loss: Sea level rise threatens 70% of coastal stopover habitat, coral reef acidification destroys tropical feeding grounds, and prairie wetland desiccation eliminates critical waterfowl breeding areas across multiple ecosystems.

- Range Contractions: Boreal birds face projected range reductions of 73%, while high-elevation and polar species have nowhere left to migrate as temperatures rise at rates 10-100 times faster than natural post-glacial increases.

- Cascading Threats: Climate change, combined with existing habitat fragmentation, the expansion of invasive species, and disease spread, creates compounded risks that exceed birds' natural capacity to adapt.

- Conservation Solutions: Protecting large contiguous habitats, restoring degraded ecosystems such as prairie wetlands, and pursuing careers in wildlife biology and conservation science are the most effective strategies for helping bird species survive climate change.

Passionate about protecting birds and wildlife from climate change? Explore degree programs in environmental science, wildlife biology, and conservation that prepare you to make a real difference in preserving bird populations for future generations.

- Invasive Species: How They Affect the Environment - February 23, 2015

- How Climate Change Affects Birds - February 11, 2015

- Environmental Consequences of Fishing Practices - February 6, 2015

Related Articles

Featured Article

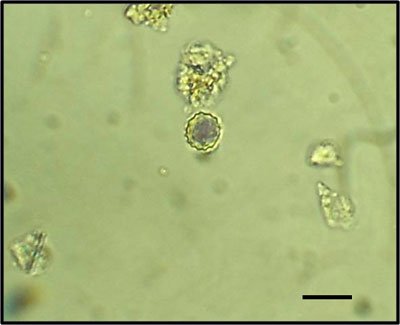

Phytoliths: What They Are and What They Tell Us